Bergman Walls and Associates

Bergman Walls and Associates Last October, the Yocha Dehe Wintun Indian Nation pulled the plug on a planned 0 million renovation of the Cache Creek Casino Resort in Brooks, California.

The project would have added a 10-story hotel and two dozen cottages, and more than tripled the number of guest rooms at the property. Suspension of the plan was “a pretty straight-ahead business decision,” said tribal spokesman Brent Andrew, based on the still-struggling economy. The tribe settled for an upgrade of the existing hotel.

The Jamestown S’Klallam tribe of Washington State, which plans a $50 million hotel complex for its 7 Cedars Casino, will not break ground for several years at least, due to the soft economy. “We have some beautiful renderings,” said CEO Jerry Allen—but that’s all they will have until about 2015.

In Buffalo, New York, the Seneca Nation recently completed a $9 million expansion of its temporary casino, which opened in 2007. But the temporary facility—with 223 more slot machines and 5,000 square feet of added gaming space—sits in the shadow of the stalled permanent casino, a steel hulk that has actually begun to rust. Construction on the $333 million permanent casino was halted in 2008, due to the economy.

And the stories go on and on. Tribal casinos that once made ambitious plans to overhaul and expand their casino properties have been forced by a historic recession and jittery lenders to base their renovation cycles on necessity alone.

According to Smith Travel Research, which compiles data for the hospitality industry, construction projects were down by more than one-third between December 2007 and September 2009. Projects on the drawing board at that time were cut by 26 percent. And beautiful renderings continue to gather dust at gaming companies around the U.S.

It’s a matter of simple math. Capital expenditures for improvements typically derive from a percentage of revenues (hotels, for example, usually reserve 4 percent to 5 percent of annual gross revenues to offset upgrades; some brand-related “refresh” programs mandate capital improvements every five to seven years).

But with revenues down 10 percent, 20 percent, even 30 percent in some sectors, discretionary expenditures are the first thing to drop off the to-do list. In an increasingly competitive industry, however, delaying essential upgrades is not an option.

When major overhauls are out of the question, tribes are staying competitive by practicing the Three R’s: refresh, renovate, retrofit.

Next to Godliness

The most cost-efficient upgrade is a soft-goods renovation—replacing pillows, bed linens, curtains, etc.

“Once you’ve taken care of fire and life safety and made sure your physical plant is running smoothly—the AC is working, there’s no leaky roof—you have to make sure everything the guests touch on a regular basis is clean: the bedspread, the duvet cover, throw pillows, linens, draperies and sheets,” says Bill Langmade, president of Purchasing Management International, LP of Dallas, the leading purchasing agent for the gaming industry. “Most gaming properties have very high occupancies—80 percent and 90 percent, where 65 percent and 75 percent is the norm. So the rooms in these hotels get beat up more quickly.” As a property ages, capital expenses and the cost of repairs and maintenance increase.

A soft-goods renovation—which also involves touching up nicked or scratched furniture and replacing upholstery and carpet—can save about 60 percent to 70 percent of the price of a hard-goods renovation.

“Leave the lighting alone,” says Langmade. “Leave the art alone, the wall coverings, the TV, but replace or repair anything that your guest feels or touches. If that’s the only thing you do to keep the decision-maker from choosing to go elsewhere, do it. Because once you lose a customer, they never come back.”

Minimal improvements can also justify rate increases, so the investment will be recouped over time.

“Refresh a room and you can expect to get an extra couple of bucks in rentals,” says Langmade. “Or you can discount the room and drive that occupancy into the casino. At least you won’t be losing money.”

Newly upgraded rooms are also cause for an ad blitz: “Come see our new look.” But there are downsides to phased renovations, Langmade says.

“You’ll get a better buy if you do all 300 rooms at once instead of 100 rooms at a time, and you certainly don’t want to be in an interminable renovation that lasts for years at a time. If you have the money, yes, it’s best to get in, get out and get it over with.

“But if you’re limited in capital, find those things that guests touch, and fix or replace them as you can. The best thing you can do for a casino is maintain it meticulously, have the greatest crew, give them tools to keep it as clean as possible, and repair as you go along.”

Price vs. Value

Lee Cagley, principal of the interior design firm Cagley and Tanner of Las Vegas, rejects the notion that effective upgrades have to come with a big price tag.

“There’s a difference between quality and expense,” says Cagley. “It’s a fallacy to say it’s easier to do a design when lots of money is involved. The work we’ve done most recently was well-priced to begin with.”

He recommends judicious spending on furniture, fixtures and equipment, economizing on some items, and splurging on those that have maximum impact.

“For years, the classic East Coast uniform for a woman was a Lilly Pulitzer dress and an Hermes scarf,” Cagley says. “In times like these, I may have to use full lead crystal in a chandelier, but I don’t have to spend $10,000 a yard on the fabric that hangs around it. You put your money in a specific place where it changes the perception of the entirety.”

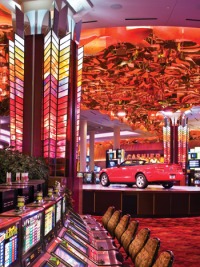

Cagley believes effective lighting is always a good investment. The goal in a casino, he says, is to keep the lighting primarily at eye level, which creates a sense of comfort and familiarity, mimicking residential lighting.

“Sometimes in casinos, the only thing at eye level that’s lighted is the slot machine face. So you have a black ceiling with down-lights that show every scrap of paper on the floor.” Far better to “layer” light at and near eye level through sconces, cove lighting, hanging lamps and illuminated columns, he says. “It’s a hard job to do, but when it’s done right, the finished space has an indefinable glow” that enhances every offering on the floor.

Though the casino is a world unto itself, a self-contained universe of entertainment, Cagley advocates a blend of the familiar and the aspirational that both soothes and excites.

“People love to try on alternate lifestyles, imagine what it would be like to be some Saudi prince or a rock-and-roller. But they also want to feel comfortable, and the point of reference for that is their home.” It’s vital, he says, to create many spaces within one space, and design pathways that lead guests to different kinds of entertainment, be it a bank of table games, a nightclub or a restaurant.

By their nature, he says, “casinos want to be great, big, huge, column-free spaces. But people don’t live in warehouses and they don’t live in barns. You want to break massive spaces into smaller units so your guests don’t feel like they’re one of 10,000 people sitting on a slot machine stool.”

Telling the Story

“Casinos are very similar to retail or theme parks from the standpoint of creating paths or walkways that draw customers along, creating excitement and interest throughout the journey,” says Tom Hoskens, principal of the Cuningham Group. “Reconfiguring gaming areas is an ongoing thing with casinos,” which constantly monitor the hot spots and dead spots on and around the casino floor.

At the recently renovated Mystic Lake Casino in Minnesota, designer John Culligan of the Cuningham Group created a dynamic, lava-like “Golden River” ceiling feature that both articulates the gaming floor and leads guests on a journey through the resort’s many entertainment venues.

Mystic Lake, owned and operated by the Shakopee Mdewakanton Sioux, is the Midwest’s largest gaming hall. Its “multi-phased, Las Vegas-style renovation” was designed to reignite the excitement for existing patrons, and entice a new demographic as well.

It’s a delicate balance, introducing new features yet retaining enough of the familiar that longtime guests—who already enjoy and patronize the venue—don’t feel excluded.

“Part of the challenge of renovation is to keep it as comfortable and as homey as you can for loyal patrons, making it better and easier to navigate,” says Hoskens, so that the change is more an improvement than a radical departure that could alienate base customers.

Though Las Vegas remains the standard, most tribal designs continue to reflect the community’s heritage and association with nature. The design at Mystic Lake included multiple natural finishes—granite, onyx, a variety of woods—to evoke the flowing water, craggy banks and verdant landscape of the Minnesota River Valley.

The same principle applied at Harrah’s Cherokee, now in the midst of a $633 million overhaul that will make its hotel the largest in North Carolina (it is one of few massive renovations that went forward despite the recession). There, Cuningham designers created “a revision of a modern Smoky Mountains lodge concept inside the casino itself,” says Hoskens, with an unfolding interior path that includes artistic representations of rivers, valleys, woodlands and mountains. They guide patrons through the space, make iteasy to explore without confusion, and recall the tribe’s history at the

same time.

“We have a slogan here, ‘Every building tells a story,’” says Hoskens. “If you tell that story correctly, you capture the soul of the place and the people.”

Timing Is Everything

In the years leading up to the recession (when all those renderings were being rendered), the building industry enjoyed a spike in both renovation and new construction. Costs of labor and raw materials soared. According to RS Means, a building costs data firm, the price of construction rose a median 8.6 percent between 2004 and 2006.

That pendulum has clearly swung in the opposite direction. According to some figures, construction costs were down 15 percent to 20 percent in fourth-quarter 2009, and construction saw the highest unemployment rate of any sector. Despite signs that the economy is inching toward recovery, many projects are currently being bid at cost or even below, and competition is keen among vendors, contractors and subcontractors.

But the trend will not continue indefinitely, and some experts predict a rush to build in 2012 that mirrors the post-9/11 recovery. This could be the time to make a deal, and ensure that your property is primed to take advantage of the rebound.