In the first Golden Age of casinos, the 1940s and ’50s, nightclubs were relatively tame hangs where men wore ties, women wore pearls, and couples swayed to the cha-cha. Today, more often than not, nightclubs are sensory blitzes of pulsing lights, pounding electronica and twentysomethings whose night doesn’t start until Cinderella is long gone.

The ubiquitous scene, born of the house and techno music explosion of the late 1980s, is going strong: according to one estimate, the worldwide club industry is now worth more than $36 billion.

But the sector has yet to rebound to pre-Covid levels ($41.2 billion) and has been further challenged by higher costs, lower discretionary income and the surge in online and mobile entertainment. Is the current model due for an update?

Follow the Money

First, a few statistics. There are an estimated 50,000 nightclubs in the U.S., charging an average $15 per cover—affordable for anyone, but it’s just the baseline.

XS at Wynn

At XS at Wynn Las Vegas, which routinely tops the city’s “best-nightlife” lists, a recent DJ set by Rufus Du Sol included a $200 general-admission cover, $300 for expedited entry. At Zouk at Resorts World Las Vegas, a table on the dance floor will set you back at least $5,000. On Memorial Day weekend at Drai’s, ringside seating for 12 at a Cardi B concert cost $15,000.

Booze is a big moneymaker. Top clubs can charge hundreds of dollars for a bottle that goes for 20 bucks at the corner store, and thousands for champagne (less taxes, tips and other fees). And some industry observers blame the high price of entertainment on superstar DJs. The highest earners, like Steve Aoki, Calvin Harris and Diplo, rake in tens of millions of dollars per year, and those costs trickle down to the club-goer.

Omnia at Caesars Palace

Yet a certain demographic has always been willing to pay, even in lean times. XS opened in 2008, during a recession that reduced overall Strip revenue by 16 percent. Even so, this “$100 million temple to revelry” started strong and soon was doing gangbuster business. By 2011, Strip beverage departments were bringing in more than $1 billion a year, inspiring more big clubs like Hakkasan at the MGM Grand and Omnia at Caesars Palace.

Those Strip palaces are more than viable—XS alone generates about $90 million in revenues per year—in part thanks to out-of-towners, for whom a trip to Vegas is usually a splurge. According to the Las Vegas Convention and Visitors Authority, one in four Sin City visitors are first-timers—that’s 10.2 million people in 2023—and they budget for extravagance.

Hakkasan at the MGM Grand

But inevitably, times and tastes change. In the U.K., the once-reliable 18-to-30 age group is less interested in the nightclub experience. Attendance is at a quarter of peak levels, and the number of clubs has dropped from more than 1,200 in June 2020 to about 870 today—a third of the inventory.

World Metrics attributes this downward trend to “a substantial shift in the social behavior and preferences of young adults,” influenced by “changing entertainment options, economic conditions and cultural trends.”

Which begs a couple of questions: What still works in the club environment? What’s become passé? And most importantly, what’s next?

Let’s Get Small

When it comes to clubs, the Gen-Z and millennial generations—including adults from age 18 to 43—remain the prime demographic. According to the American Nightlife Association, more and more, these patrons are after “experiential dining and alternative entertainment,” not impersonal raves that can cost a mortgage payment and more.

The model may have stumbled even before the pandemic. In a 2020 article in Rolling Stone, club entrepreneur Gideon Kimbrell called Covid “the outsized straw that broke the camel’s back.” He said the slide began with oversupply and a “slow-building tsunami of disinterest in jam-packed clubs… Hipsters and new money are now seeking more intimate lounges, bespoke experiences and upscale restaurants.”

John Ruiz, principal at R2Architects, has witnessed the same phenomenon. He calls it “an evolution that’s been going on for some time and is picking up more momentum.”

Club patrons these days “are overwhelmingly experience-seeking—visually, audibly, aromatically, etc.,” says Ruiz. “They seem to be looking for more social interaction in a more comfortable setting, which blends an energized social scene fueled with music along with food and beverage.”

Smaller entertainment concepts are cropping up, like lounges with live bands and/or DJs that “energize the venue and the adjacent spaces.” Guests can enjoy closer quarters with subdued lighting in an atmosphere that lends itself to actual conversation. Enhanced by music, these smaller venues have a “club vibe” that some may prefer to loud, crowded spaces the size of the Superdome.

The trend “isn’t new,” says Ruiz, “but in our opinion it’s getting more traction in casinos and non-gaming establishments.”

What’s New

In June 2018, the Hard Rock Hotel and Casino opened on Atlantic City’s famous Boardwalk, at the site of the former Trump Taj Mahal. But less than two years later, it had to shut down due to Covid-19. The resort was dark for four months, and reopened without its nightclub, DAER, which never returned.

That’s all changing with the debut this summer of the Balcony, described as an “upscale, VIP nightlife experience” that dazzles on a smaller scale. Hard Rock AC President George Goldhoff calls the Balcony “a hybrid lounge and nightclub, really boutique-y,” with indoor and outdoor spaces and compelling, complementary vibes.

The club was created in response to customer demand. “We’ve done consumer research and focus groups of our highest-end players,” says Goldhoff, “and they all said the same thing: ‘We love the entertainment here at Hard Rock, you do such a fantastic job, but you don’t have a proper hybrid lounge-nightclub.’ That’s what they asked for, and we listened.”

The Balcony’s primary demo isn’t the coming-of-age crowd, but adults 28 and up: Gen Z and millennials, who spend more on entertainment per year than other age groups, and may be more likely to sample other amenities on property: the hotel, the restaurants, the casino, and the resort’s concert arena. Says Goldhoff: “I can’t underestimate the power of driving 6,000 people into Hard Rock Live, then giving them a place to continue their evening.”

While VIP perks are available, he adds, “Not everyone needs bottle service. I was just on the website of a casino in Las Vegas, where you can get a six-pack of Budweiser for $140. That’s absolutely ridiculous—and irresponsible as far as I’m concerned in this market.”

He acknowledges that the mega-club concept isn’t going away: “There’s a place for it, 3,000 people dancing to EDM or deep house music. But we’re going in the other direction, really leaning into that upscale nightlife destination with personalized service.

“You can go in and sweat and dance to the music. When you want a respite, you can go out and relax at our beautiful outside bar. There’s a cool ocean breeze. You’re looking at the Atlantic Ocean. The lighting is perfect. It’s a completely different feel.”

The Balcony also is “a better mousetrap. And it’s going to be a differentiator in Atlantic City, because nobody else is doing it.”

User-Friendly

Nightlife impresario David Pena, founder of the famed Boogie Nights franchise, says a lot of clubs can go stale in as little as three to five years. To survive, owners must “constantly change their name, change their formula and change their look, because we’re all serving up the same product.

“That’s why I’m so grateful for the longevity Boogie Nights has had—it’s not by accident.”

Pena created the enduring brand in 2007, calling it the “Ultimate ’70s and ’80s Dance Club.” It’s since expanded its playlist to include music of the ’90s and post-2000s—rock and pop, disco and R&B, hip-hop and new wave—a mix that draws partiers across multiple generations.

“Especially in casinos, a lot of nightclubs are geared towards 21- to 28-year-olds,” says Pena. “We wanted a big ‘umbrella,’ a place that would attract all different ages and styles of music. Boogie Nights is more than a nightclub. It’s a movement of sorts, and we work really hard to keep it relevant.”

Pena rejects the exclusive “velvet rope” mentality immortalized by Studio 54, the decadent New York club that took snobbery to a new level, limiting entry mostly to celebrities and the Beautiful People.

“In this day and age, it’s not cool when people are snooty and don’t engage—some places make you feel you’re lucky to even get in the door. I hate that type of feeling,” says Pena. “It was a great gimmick for Studio 54, but not everybody is Steve Rubell.”

At Boogie Nights, inclusivity is the name of the game, “and that’s what people have come to love.

“A lot of casino executives have told me they love Boogie Nights because it has a wide demographic and appeals to all of their customer base”—not just the party-hearty kid crowd.

The Big House

Big clubs have a lot going for them, including must-see spectacle, especially in Vegas.

Omnia, designed by the Rockwell Group, is massive at 75,000 square feet—bigger than a football field—but carves that space into three lounges: a main room and mezzanine, and a rooftop terrace with dazzling views (inspired by, of all things, Shakespeare’s Midsummer Night’s Dream).

Adding to the wow factor is an 11-ton chandelier with smart lighting that pulses to the music. And if bottle service is pricy, it’s fun to see your drinks dropped in from the ceiling by aerialists.

Other big clubs incorporate smaller-scale venues for people who want a change of pace. Hakkasan touts “five levels of refined decadence,” linking the main nightclub to a mezzanine, a lounge and a pavilion. Then there’s the Hakkasan Grid, home of the largest permanent kinetic light installation in the U.S.—a shape-shifting overhead showpiece shared so often on Facebook and Instagram that Hakkasan technical director Gerardo Gonzalez “consciously wove social media perceptions into the rendering phase… and put a rendering of the Grid inside a phone to see how it would look in a social media post.”

In the digital era, bars and smaller nightclubs also use light and sound to create an immersive guest experience. At the Balcony, says Goldhoff, “We’re really differentiating ourselves through our lighting design and pixel-mapping—projecting images onto screens throughout the interior of the space, which provides a lot of stimulation.”

The Future is Small

By one estimate, the U.S. nightclub industry could grow to $38.2 billion by 2028—still short of the pre-Covid peak, but buoyant, with the promise of longer-term growth as operators keep pace with consumer needs.

As Kimbrell advised in 2020, “Even if you still have a viable business plan for a mega-club, I recommend diversifying into smaller clubs, lounges or upscale restaurants that rely on original programming (not just headliner DJs) and allow for people to converse and hear each other.”

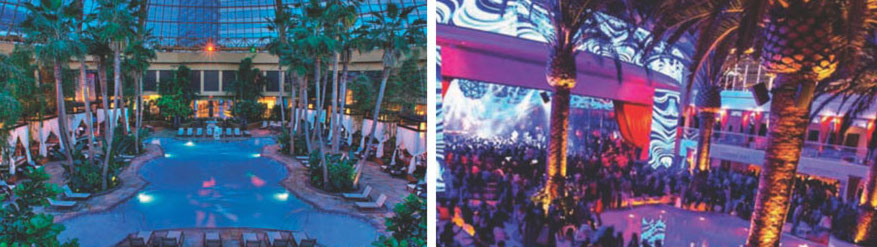

Double-dipping: When the sun goes down, the Pool at Harrah’s AC (left) and Drai’s at the Cromwell in Las Vegas do a quick change from day club to nightclub

Pena adds, “Don’t price yourself out. Some people make the mistake of thinking the more we charge for a bottle the more we’re going to make. That’s unrealistic. Your customers know what a bottle of booze is worth.

“Sometimes people splurge, but they can’t do it every weekend—and the less bodies that show up, the less the club looks busy. I’d rather have a full nightclub, give customers the best value and know that they’re going to come back. Then your customer base keeps piling on and piling on. That’s the key: volume and consistency.”

R2Architects principal David Rudzenski concludes, “Covid changed things. Even today some people won’t go to giant clubs with shoulder-to-shoulder crowds. We’re looking at a future of smaller, more intimate clubs.”