For a large percentage of casino patrons, buffets have become a ubiquitous aspect of the resort experience. This is mainly attributable to the fact that the two have been largely intertwined since the Truman administration.

The long-defunct El Rancho in Las Vegas is largely credited with opening the first traditional casino buffet—the Buckaroo Buffet—in 1946. For several decades afterward, the concept exploded in popularity in Las Vegas and beyond as operators and patrons alike came to love the all-you-can-eat smorgasbords.

For casino owners, buffets answered the challenge of giving customers what they want by giving them everything, in one place, all at once. Buffets covered all meals and preferences, and over time grew so wide-ranging that even the pickiest gamblers could build a full plate before returning to the action, which is the ultimate goal of any casino amenity.

Players loved the variety and convenience of being able to feed everyone in the family at once. There’s also a deeper psychological element—in a casino, the odds are inherently stacked against you, and a buffet seems like a guaranteed value proposition. You might lose your bankroll on a double zero or crap out on your first throw, but unlimited prime rib for a decent price can make an unlucky trip a little easier to stomach.

But over the years, as competition grew and demographics changed, the traditional buffet model faded away in favor of decentralized, multifaceted food halls. Don’t be mistaken, though—these are not food courts, the sterile mall variants from our youth.

With food halls, designers and operators have elevated the food court experience to feature curated selections of globe-trotting cuisines, often utilizing unique local vendors in the process.

Buffets were long accepted to be loss leaders, whereas food halls have the potential to become profitable amenities that generate repeat customers, kickstart conversation and create new experiences for the next generation of guests.

Changing Customers, Changing Tastes

Several key factors have influenced operators’ decision to migrate away from buffets. These include operational difficulties, general food-and-beverage trends, the onset of Covid and just a general urge to rebrand and refresh.

“I would say (the change) has been on the table with pretty detailed analysis at a lot of properties for a long period of time,” says Matthew Chilton, founding partner of GMA Consulting. “The marketing media has a big influence on this growth of unique, awesome cuisine experiences… A lot of the properties just saw the numbers dwindling down and asked, ‘What’s driving this?’”

As he explains, one of the biggest answers to this question was the advent of grab-and-go outlets such as Starbucks that have “grabbed big wallet share from everyone,” especially for the breakfast segment, a huge driver for buffets in particular. These quicker outlets have also gradually swayed midweek business travelers, who “don’t have an hour, hour and a half” for long lines and marathon meals.

The desire to have just a little bit less is indicative of a younger, fitter crowd. “From the old days of all-you-can-eat, there’s been a shift into a little more health-conscious, elevated food experience, steering away from the gluttony into more of a pick-and-choose,” Chilton says.

Jeff Wynkoop, senior project manager for R2Architects, says the answer of why casinos eschew buffets “really depends on the size and location” of a particular property. He points out that the decline of buffets in Atlantic City, for instance, was mainly due to business challenges.

“When Atlantic City casinos stopped providing day-tripper busing packages, which included the buffet lunch and dinner, buffets were closed or greatly reduced,” he says. “The focus shifted because of reduced volumes of patrons to capture them at cash-paid food venues… Gone are the free or comped-to-the masses buffets.”

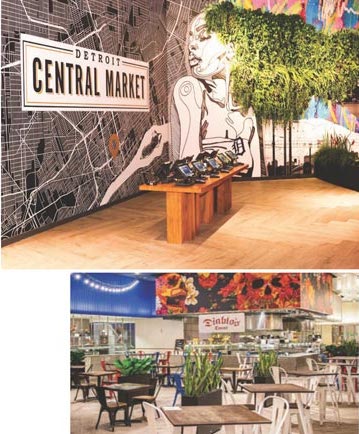

The food hall at MGM Grand Detroit

Any mention of health and business challenges must also include Covid-19, the ultimate combination of both, and the final nail in the coffin for a good number of buffets around the industry. Forced closures put everything into perspective and forced operators to think about the longstanding downside of operating buffets. Some responded by downsizing, while others opted to go in a different direction altogether.

Chilton says Covid “served as a golden kind of opportunity, once (operators) knew that things were coming back, to have a reinvestment or a significant shift” in their food-and-beverage strategies.

One example of the post-Covid shift happened at MGM Grand Detroit, which partnered with R2A to transform its former Palette Dining Studio buffet into the Detroit Central Market food hall, which opened in March 2022. The 4,500-square-foot venue changed both the look and feel of the space as well as the technology behind it, allowing guests to order and pay directly from their tables rather than the self-serve buffet model of the past.

Making the Leap

For those who forego the traditional buffet model for a more creative food hall design, the benefits are wide-ranging.

From an operational perspective, food halls are considered much more economically viable than buffets, perhaps the chief consideration for any aspect of the business. Food halls generate more revenue in some areas and save money in others, and they also provide opportunities to draw in third-party leased vendors who can reduce risk.

David Nejelski

“Food halls give our clients more profit than their counterparts,” says David Nejelski, vice president and creative director for TBE Architects. “Guests select the food they want and pay for each dish either at the selected venues or as they leave the hall.” Buffets, on the other hand, cause diners “to take more than they will eat, and in doing so there’s room for more waste and profit loss. Additionally, food halls tend to offer a higher quality of food, elevating the guest experience.”

Individual purchases at multiple vendors increase customer spend while also encouraging repeat visitation. This, Chilton says, is where food halls can really shine—properties can “elevate the price per customer” as patrons grow curious to explore new things—an improvement over the “assembly line” atmosphere buffets sometimes foster.

There are also cost-saving elements to be gleaned from food halls, and these are often unlocked with a solid pre-build design and layout process, according to Wynkoop.

“Economies of shared services can come into play as in shared drink lines or shared condiment stations, both of which reduce duplication and area to reduce the cost to build,” he explains.

The decentralized nature of food halls encourages wandering but presents a tricky puzzle to solve with regard to seating arrangements. This, too, requires some forethought and planning to find the best solution for the available space.

“The biggest challenge to overcome is a unified seating area that supports each varied food venue throughout the course of a day while at the same time not getting too large,” Wynkoop maintains. “There seems to be a tendency to overbuild the seating counts, and therefore the space becomes unwieldy and loud. Constraints must be used to scale correctly.”

A related factor operators must consider when laying out the space is the point-of-sale location. Food halls allow for optionality in this way as well.

The Kitchen at Quil Ceda Creek Casino in Tulalip, Washington

“Guests can expect to pay in one of two ways: at each food venue or as they exit the food hall,” says Nejelski. “As a design firm, we work with our clients to decide the best point-of-sale option and create the layout of the space accordingly.”

TBE, in partnership with Rippe Associates, opted to go for single-payment touchpoints for the Kitchen at Quil Ceda Creek Casino in Tulalip, Washington. Guests pay for all selections at one time at the innovative food hall venue, which features 212 seats and eight food options ranging from seafood to steaks, pizza, sandwiches and more. The venue also boasts the region’s first greaseless kitchens, incorporating “energy-saving wind-speed and induction cooking technologies,” the firm says.

Making Connections

Aside from bottom-line considerations, food halls also allow operators to continuously mix and match various vendors and types of food, creating new experiences while in many cases bringing in local vendors to help establish connections to the community and drive engagement.

Nejelski points out that these venues “present many options for types of food and aesthetics,” helping both operators and designers to “lean into branding identity opportunities for the property.”

For example, TBE’s Kitchen at Quil Ceda boasts a wide range of locally sourced options in its menus, including berries from Skagit Valley farmers, Umpqua Dairy products, breads and buns from Montana Wheats, and soups from the Ivar’s chain in Seattle.

R2A’s Detroit Central Market project follows this same idea by featuring four home-grown outlets, including Detroit Wing Company, Grand Wok Noodle Bar, National Coney Island, Diablo’s Tacos and of course, Detroit-style pizza from the Corners.

In a statement announcing the opening of the hall, MGM’s Midwest President David Tsai said it was “yet another way we’re dedicated to providing guests with new and uniquely Detroit experiences.”

For Chilton, these types of projects really hit on what it takes to succeed at the highest level of hospitality, keeping things new and exciting while also helping to improve the business.

“You can tell a story, and that’s what hospitality’s about: telling stories to try and invigorate the customer, but also make a little bit more profit,” he says.

The infusion of these established, standalone brands can also take some of the burden off operators who, in some cases, may have dozens of other dining options on their property that they already have to promote and market. This dynamic highlights the challenges of orchestrating an effective food-and-beverage ecosystem.

“Some of these places have upwards of 20 to 30 different experiences, and what the customer wants is that variety,” Chilton says. “But each of them, whether they’re owned in-house or outsourced, is battling for that customer.

“The restaurant business is tough, and you have to be constantly reengaging. It’s a constant dance. Food-and-beverage is probably one of the hardest individual kinds of entities because it’s so dynamic, so changing. You’re scrapping for small margins and it’s just based on large costs.”

Buffets may be easier to market, but they can be more difficult to adapt. They’re more static, whereas food halls are largely leased and can therefore be interchanged depending on trends and performance. Most casinos have no issue filling those spaces with eager bidders. It’s an attractive alternative to always having to reinvent the wheel with large capital expenditures.

And for the venues that do grow and become the next big hit, it forms yet another bond to the community and patrons that can pay dividends for years to come.

“There’s very much a relationship side of this, where you find if you have a good relationship, good operator, lots of communication, lots of transparency, you can be constantly thinking of ideas,” Chilton notes. “That’s what food-and-beverage people do.”